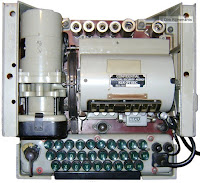

|

| TSEC/KL-7 Photo © D. Rijmenants |

One such case was civilian radio officers on merchant ships during the 1982 Falklands War. The Falkland Islands (Malvinas in Spanish) is British overseas territory, disputed since long by Argentina. On April 2, Argentina invaded the Falklands, and the British government sent a huge naval task force with two aircraft carriers, 65 Royal Navy and Fleet Auxiliary vessels, 62 merchant ships and two ocean liners that carried two brigades.

To sail that task force 6500 nautical miles or 12.000 Km across the Atlantic was an enormous logistic operation and they needed vast quantities of fuel for the trip and to keep the task force operational near the Falklands. The British Ministry of Defense chartered a large number of commercial merchant ships to support the operation, a procedure called STUFT (Ships Taken Up From Trade).

One of these STUFT ships was the Eburna tanker that carried fuel oil, diesel and aviation fuel which had to be transferred by RAS (replenishment at sea) to other ships. This involved two ships steaming alongside each other at close range while maintaining a steady speed throughout complex anti-submarine manoeuvres. The communications between the task force and the STUFT ships had to be secure and the Eburna radio room received a KL-7.

|

| The Eburna fuel tanker (source: helderline.com) |

Their KL-7 had an extension to read punched tape and they attempted to receive

traffic by setting the teleprinter to copy to both tape and paper, but as traffic was too heavy and mixed with messages from many other ships they had trouble separating the punched tapes correctly. They therefore let the teleprinter simply print the messages and then typed the ciphertext onto the KL-7. The deciphered text, printed on gummed tape, was stuck onto a message form and

delivered to the captain, although they sometimes had to translate the "navy-speak" into plain English to make it understandable to their civilian captain.

The system indicator "FDDND" was

always the first group of ciphertext. They would set up the KL-7

following the key setting instructions for that day, then switch it to

"P" and type in that group, then switch to "E" and do the encryption. The daily machine settings were printed in a booklet which had the edges of all its pages stuck together, one page per day and one month per

booklet. To set up the machine you would peel off the sheet from the previous day, revealing today's settings. Used key sheets were torn off and incinerated.

Eburna's KL-7 was supplied with only one rotor cage and one set of rotors. According to the instructions, the rotor setting were changed at 00:00 UTC and the key sheet of the previous day had to be destroyed. Thus, when a message of the previous day arrived a few hours later, they could not go back to the old settings. They decided to keep the old key sheet for an additional 24 hours to go back if they had to. In the military, the KL-7 was usually supplied with two rotor cages, and the rotor cage with settings of the previous day was kept the next day. Going back then simply meant swiftly detaching the current cage and attaching the old one. The Eburna radio office did not have this luxury.

The KL-7, rotor set and setting instructions were supposed to be kept in the safe but the Eburna didn't have a safe, so they kept them in a cupboard. They assumed there were very few spies running around in the middle of the South Atlantic and their solution was probably secure enough. Bernard also recalled rewiring at least one of the rotors every month, and that it

was quite a fiddly task involving many small parts.

Bernard also commented on the KL-7 simulator. "I downloaded

the KL7 simulator and am having fun with it reliving old memories. The

only thing the simulator doesn't do that the real machine did is to fail

occasionally (actually quite often!) due to dirt under the keyboard. In

accordance with Murphy's Law it would always do that when urgent

traffic was on hand. Then there was nothing for it but to take the

machine apart and clean it out". The need for intensive maintenance was

indeed one of the KL-7's disadvantages and essential to avoid the so-called

dead-rove.

The Navy didn't quite understood how merchant ships operated or how they were equipped, and never

realized that keeping a 24 hour radio watch with only two men for the duration of the

entire campaign was a daunting task. The Navy also expected them to know how to handle

a tactical radio net and encrypt figures and phrases

using NATO code books.

At first, Bernard had no idea what was going on, and

it took several days to work it out. He noted that a tactical radio net in a war zone is not the best place to

learn military radio procedure. To their excuse, the Navy also had a daunting and unprecedented task to compile a huge naval task force within days.

The Eburna story is a rare example of civilian merchant radio

officers that worked with the KL-7. Undoubtedly, more people outside the military, intelligence and state departments worked with

this beautiful cipher machine. Let's hope their stories will also be recorded some day, before that fascinating history is lost. In the end, the Argentine forces surrendered after 74 days and many lives were lost on both sides. The 1982 Falklands War was probably the last time the KL-7 was used during combat operations.

Read The KL-7 on Merchant Ships during the Falklands War (pdf), the story from radio officer Bernard Kates.

More about the KL-7, including all technical details, its development, the operational history, and many original NSA, ASA, AFSA, FBI, CIA and NATO documents at the TSEC/KL-7 ADONIS & POLLUX page

More about the Eburna tanker at Helderline.com and a detailed history of the Falklands War is available at Naval History.

Call to Signals Veterans! If you worked with the KL-7 as operator or technician, we're interested in your experience with the machine, to expand its history. The KL-7 is fully declassified and we are not interested in classified information, only stories about where and how you worked with the KL-7 . Since the KL-7 retired more than 40 years ago, time is running out to document personal testimonies. If you have a story to share, then please contact us through the contact page on our website Cipher Machines and Cryptology.

Let's preserve cryptologic history!

To

get an idea of the kind of stories we would like to document, check out

other published stories, also available at the KL-7 webpage:

Enjoy reading!

Excellent article, I enjoyed reading it very much. Thanks!

ReplyDelete