|

| Mounted camel guard at the refinery. Source: BAPCO |

The Bahrain Petroleum Company (BAPCO) was a Canadian subsidiary, founded in 1929 by the American Standard Oil of California (Socal) to run its operations at the Awali oil fields on Bahrain Island, at the inlet of the Persian Gulf.

BAPCO became a possible target of Axis forces when Britain declared war on Germany. In 1940, the Bahrain oil refinery was targeted by Italian bombers, forcing the Allies to strengthen Bahrain's defense. Bahrain, in 1943 still a British Protectorate, decided to implement a censorship on messages that were sent over commercial cable and wireless, to prevent disclosure of information that might be useful to the enemy.

This censorship, however, greatly restricted the communications and operations of BAPCO. The majority of their messages contained information about oil production, shipping, personnel and food supply. Those messages fell into three main categories: a) cables that could be sent in plain text without objection, b) security cables that contained information that, in conjunction with other information, might indirectly be useful to the enemy, and c) secret cables that would be of direct use to the enemy if intercepted, such as ship movements, especially oil tankers.

BAPCO became a possible target of Axis forces when Britain declared war on Germany. In 1940, the Bahrain oil refinery was targeted by Italian bombers, forcing the Allies to strengthen Bahrain's defense. Bahrain, in 1943 still a British Protectorate, decided to implement a censorship on messages that were sent over commercial cable and wireless, to prevent disclosure of information that might be useful to the enemy.

This censorship, however, greatly restricted the communications and operations of BAPCO. The majority of their messages contained information about oil production, shipping, personnel and food supply. Those messages fell into three main categories: a) cables that could be sent in plain text without objection, b) security cables that contained information that, in conjunction with other information, might indirectly be useful to the enemy, and c) secret cables that would be of direct use to the enemy if intercepted, such as ship movements, especially oil tankers.

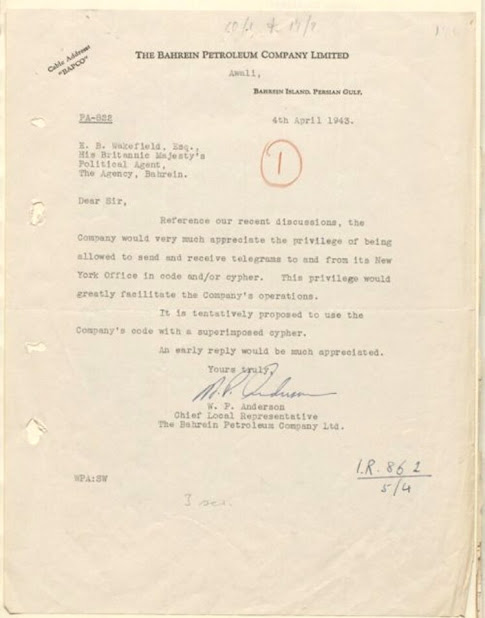

On April 4, 1943, Ward P. Anderson, the general manager and chief local representative of BAPCO, asked E. B. Wakefield, the British Political Agent in Bahrain, permission to encrypted their cables between the local branch and their New York office. This would allow them to send security related cables, at the same time respecting Bahrain's

censorship. Anderson proposed a secret company code, superimposed (enciphered a second time) with a transposition cipher for added security.

The Political Resident of the Persian Gulf in Camp Bahrain forwarded the request on April 8 to the Secretary of State for India in London, who approved the use of a secret code, provided that censorship received a plain text version of all messages, sent in that code, BAPCO should continue to send messages through the Navy if they contained vital information that would be of direct use to

the enemy, and messages regarding political matters were to be sent through the Political Agent. After consulting the New York office, Ward Anderson agreed to these conditions.

P.A.I.C. in Baghdad asked whether the code had already been vetted for security. As this was not the case, the British Political Resident forwarded the request to SNOPG (Senior Naval Officer in the Persian Gulf) in Basra but they had no officer qualified to vet the code. Therefore, PAIFORCE suggested to vet the code.

The new code, proposed by the California Texas Oil Company, arrived from New York on October 24, and Bahrain forwarded the code on November 10 by courier for examination to the Cipher Security Officer of P.A.I.C. in Baghdad. After reviewing the code, the Security Officer responded that the code offered little resistance against cryptanalysis and provided no security whatsoever.

Note: P.A.I.C. (Persia and Iraq Command) in Baghdad was the headquarters of PAIFORCE (Persia and Iraq Force), the British and Commonwealth military formation in the Middle East from 1942 to 1943.

P.A.I.C. in Baghdad asked whether the code had already been vetted for security. As this was not the case, the British Political Resident forwarded the request to SNOPG (Senior Naval Officer in the Persian Gulf) in Basra but they had no officer qualified to vet the code. Therefore, PAIFORCE suggested to vet the code.

The new code, proposed by the California Texas Oil Company, arrived from New York on October 24, and Bahrain forwarded the code on November 10 by courier for examination to the Cipher Security Officer of P.A.I.C. in Baghdad. After reviewing the code, the Security Officer responded that the code offered little resistance against cryptanalysis and provided no security whatsoever.

Note: P.A.I.C. (Persia and Iraq Command) in Baghdad was the headquarters of PAIFORCE (Persia and Iraq Force), the British and Commonwealth military formation in the Middle East from 1942 to 1943.

Surprised by this answer, Ward Anderson explained that the code was allocated by the U.S. Navy Department and considered the most secure known, used for the most secret messages. He clarified that "each page of the pad of sheets is used only once and destroyed after use". He continues, "In fact, the code changes with each succeeding letter of the message. When the pad is exhausted, a new set of pads is produced".

To Anderson, it seemed unlikely that British military authorities would be unfamiliar with the proper use of this type of code, so he asked to verify whether the code was indeed insecure, adding that U.S. authorities would be most interested if the British claims proved correct.

This was probably his polite way to hint the Political Agency and the PAIFORCE Security Officer that they were going to embarrass themselves. To their defense, it might be possible that the code was not accompanied with the complete and proper coding instructions, thus failing to show that the code was for one-time use.

To Anderson, it seemed unlikely that British military authorities would be unfamiliar with the proper use of this type of code, so he asked to verify whether the code was indeed insecure, adding that U.S. authorities would be most interested if the British claims proved correct.

This was probably his polite way to hint the Political Agency and the PAIFORCE Security Officer that they were going to embarrass themselves. To their defense, it might be possible that the code was not accompanied with the complete and proper coding instructions, thus failing to show that the code was for one-time use.

Soon after, the Secretary of State for India in London informed the Political Resident in Bushire, Iran, that the U.S. Chief of Cable Censorship urgently requested permission to use the code, adding that it was a one-time pad, similar to the one used by the Ministry of War Transport in London. P.A.I.C. also received note of this. Apparently, someone pulled some strings.

Subsequently, the Political Resident confirmed to its agency in Bahrain that the code was indeed a one-time pad from the U.S. Navy Department. Eventually, the agent informed the BAPCO representative that objection to the code had been withdrawn and that "the one-time pad can be used on the understanding that the pad is not worked through more than once".

Subsequently, the Political Resident confirmed to its agency in Bahrain that the code was indeed a one-time pad from the U.S. Navy Department. Eventually, the agent informed the BAPCO representative that objection to the code had been withdrawn and that "the one-time pad can be used on the understanding that the pad is not worked through more than once".

BAPCO started using the one-time pads as of January 15, 1944, more than

eight months after their initial request. Yes, even during wartime,

bureaucrats persist. Of course, we have to take in account that transportation and communication means in 1943 were quite different from today, and codes were always transferred safe-hand by courier.

Once the war had ended, BAPCO requested on August 22, 1945 permission from Bahrain to commence the use of the company's own cable code again, as used before the outbreak of hostilities in 1939.

Below one of the BAPCO coded messages from Bahrain to New York, with plain version included, submitted to Censorship as agreed with British authorities.

These archived conversations are a rare example of a commercial firm using the unbreakable one-time pad in the early 1940s. At that time, the use of such strong encryption was generally limited to governments, their military, intelligence agencies and diplomacy. BAPCO's use of one-time pads, allocated to them by the U.S. Navy Department, is a nice example of how government and commercial firms teamed up to ensure the highest level of communications security for those companies that were somehow important to the war effort.

All letters and cables regarding this request for using one-time pads are found in the British Library: India Office Records and Private Papers as File 10/5 BAPCO CODES, reference IOR/R/15/2/423. More examples of coded messages and their plain text version, submitted to censorship, are found in File 10/23 Code Messages - BAPCO, reference IOR/R/15/2/450. These records are archived in the Qatar Digital Library. More on the 1940 bombing raid on Bahrain in the Qatar Library, and an account of the attack on the BAPCO refinery is available at the Saudi Aramco website.

These documents are also unique as a reference, because the use of one-time pads is hardly mentioned in official documents from that era (for obvious security reasons) and they are, as far as I know, the earliest I came across. They confirm the use of one-time letter pads by Political Residents of the British Imperial Civil Administration, the British Army, the Ministry of War Transport in London and the U.S. Navy, at least as early as 1943. Both British and U.S. authorities were quite familiar with the system and surprisingly even shared it with commercial firms. The archives also show that British Residents in the Middle East regularly received sets of two-way one-time pads.

More historical and technical information about one-time pad is available at my Cipher Machines and Cryptology website.

Once the war had ended, BAPCO requested on August 22, 1945 permission from Bahrain to commence the use of the company's own cable code again, as used before the outbreak of hostilities in 1939.

Below one of the BAPCO coded messages from Bahrain to New York, with plain version included, submitted to Censorship as agreed with British authorities.

These archived conversations are a rare example of a commercial firm using the unbreakable one-time pad in the early 1940s. At that time, the use of such strong encryption was generally limited to governments, their military, intelligence agencies and diplomacy. BAPCO's use of one-time pads, allocated to them by the U.S. Navy Department, is a nice example of how government and commercial firms teamed up to ensure the highest level of communications security for those companies that were somehow important to the war effort.

All letters and cables regarding this request for using one-time pads are found in the British Library: India Office Records and Private Papers as File 10/5 BAPCO CODES, reference IOR/R/15/2/423. More examples of coded messages and their plain text version, submitted to censorship, are found in File 10/23 Code Messages - BAPCO, reference IOR/R/15/2/450. These records are archived in the Qatar Digital Library. More on the 1940 bombing raid on Bahrain in the Qatar Library, and an account of the attack on the BAPCO refinery is available at the Saudi Aramco website.

These documents are also unique as a reference, because the use of one-time pads is hardly mentioned in official documents from that era (for obvious security reasons) and they are, as far as I know, the earliest I came across. They confirm the use of one-time letter pads by Political Residents of the British Imperial Civil Administration, the British Army, the Ministry of War Transport in London and the U.S. Navy, at least as early as 1943. Both British and U.S. authorities were quite familiar with the system and surprisingly even shared it with commercial firms. The archives also show that British Residents in the Middle East regularly received sets of two-way one-time pads.

More historical and technical information about one-time pad is available at my Cipher Machines and Cryptology website.

The Bahrain Petroleum Company (BAPCO), one of the oldest oil companies in the Middle East, was established in 1929 by Standard Oil Company of California. BAPCO obtained in 1930 the only oil concession in Bahrain. In 1936 they discovered the Awali oil field and opened a refinery with a capacity of 10,000 barrels per day. That same year, Standard Oil Company of California signed an agreement with Texaco, creating the joint venture California Texas Oil Company (Caltex). These companies are now known as Chevron and Texaco. The Bahrain government took over all BAPCO shares in 1980 and acquired full ownership in 1997. Visit their website to read BAPCO's history.

Nice work Dirk! Very interesting reports. The wartime US Petroleum administration used the M-131-A (Sigtot) OTP teleprinter.

ReplyDelete