|

| Adcock four element antenna array WWII Naval direction finding station (source: Frontline Ulster) |

Directional antennas find the bearing of a signal. Early simple loop antennas had to be turned mechanically to find the signal bearing. With two or more such antennas on different locations, the target is located at the crossing of those bearings, but it was a cumbersome task. Later, double loop antennas and Adcock antenna arrays with four elements improved performance, but many more special direction finding (DF) antennas were built to locate signals, and some were quite extraordinary.

German Wartime Research

|

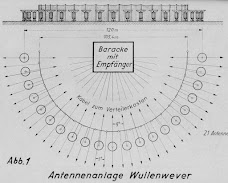

| The Wullenweber antenna array (source: FGCRT) |

The first Wullenweber, build in Skibsby in northern Denmark, was designed as high-frequency direction finding (HF/DF) antenna array and operated in the 6-20 MHz range. The above drawing shows, at the top, the view of the antenna array and the reflector screen wires behind them (click image to enlarge)

|

| First Wullenweber at Skibsby site (source unknown) |

The Foundation for German communication and related technologies (main page) has a description of the Wullenwever (original spelling), including German Naval research on Wullenwever (pdf p11-20) and the Landsberg-Lech conference (pdf) with technical details and several photos of the Skibsby Wullenweber site.

German Technology in Soviet Hands

Many German scientists were rounded up by US and Soviet forces in the final days of the war. Both were interested in this new CDAA technology, but the Soviets were the first to start building them in 1951 with assistance of German scientists.

The Soviets eventually build 31 CDAA's of various types and called them KRUG. They were placed in Russia, Warsaw Pact countries, Mongolia, Cuba, Vietnam and Burma. These KRUG stations tracked radio communications of US and NATO reconnaissance aircraft and nuclear bombers. GlobalSecurity has info and photos on Soviet KRUG antenna arrays.

The Global U.S. Antenna Network

One of the German antenna researchers was moved to the United States to assists in the development of a CDAA. The US version of the Wullenweber was the AN/FLR-9 antenna, nicknamed "Elephant Cage". The first was built in 1962 at the RAF Chicksands base in the UK, leased by the US Air Force.

|

| FLR-9 at USASA Field Station Augsburg, Germany (source: US Air Force ISR) |

The huge FLR-9 antenna had an outer diameter of 440 m (1,443 ft) and height 37 m (121 ft). A network of eight FLR-9 was constructed in Alaska, England, Germany, Italy, Japan, Philippines, Turkey and Thailand. This network could accurately locate HF signals anywhere on Earth, to track enemy airplanes, ships or ground based transmitters, but also to follow own or friendly targets.

The US Naval Security Group operated the AN/FRD-10, also a Wullenweber antenna but smaller than the FLR-9. Its outer diameter was 263 m (863 ft). A network of sixteen FRD-10's was located at coastal lines of the Pacific and Atlantic on US mainland and Alaska, Hawai, Puerto Rico, Canada, Panama, Japan, Spain and Scotland.

More about the Wullenweber

FLR stands for Fixed Countermeasures Receiving. FRD stands for Fixed Radio Direction-finder (see JETDS designations). More about the FLR-9 on FAS and Freedom Through Vigilance Association (USAFSS). Navy Radio has details of the AN/FRD-10. There's a report on the dismantling of the AN/FLR-9 at Misawa air base in Japan and the decommissioning of Joint Base Elmendorf-Richardson in Alaska (video). See also locations of AN/FLR-9 antenna system at the Station Hypo website.

More on WWII direction finding at the RSS Secret Listeners website and on Frontline Ulster's WWII Aircraft Direction Finding in the UK.

The NSA video below explains the history and purpose of the FLR-9.

The American Forces Network Pacific gave a look inside Misawa’s FLR-9, build in 1962. The antenna was demolished in 2014.

More on Signals

Many different signals were sent, received and analyzed during the Cold War. Below some posts on this blog about Signals Intelligence (SIGINT), but there's much more to discover...

Many different signals were sent, received and analyzed during the Cold War. Below some posts on this blog about Signals Intelligence (SIGINT), but there's much more to discover...

- Mysterious Cold War signals Fascinating signals revealed

- Field Station Berlin ASA/NSA listening post

- Russia’s Modern Early Warning Systems

- Electronic Intelligence at NSA History of ELINT

- More posts about signals intelligence...

Visit also the Cold War Signals page about the battle over radio waves on our website